Relating to a coworker about how hard it is for me to transmit certain values absent a cultural context, with how deeply ingrained they are as part of my religious upbringing, in pondering this reality it becomes easy to understand why so many people—myself included, at times—assume their own moral framework is universal, something everyone else must naturally share.

This moment of realization tied to a broader observation about value systems and how wildly different various religious traditions really are despite sharing some of the same foundational texts—they are fundamentally and irrevocably different. And yet because the texts overlap, some people mistakenly treat those systems as essentially similar—or even interchangeable—overlooking the profound divergences in interpretation, emphasis, or lived practice that centuries of distinct cultural evolution in these systems of thought have produced.

I plan to make three stops: one in the frame of contemporary Western thought, the next from the time of Jesus, and lastly with the patriarch Abraham. And with each of these stops explore how shared origin can mask strikingly divergent ethical worlds, and why recognizing those differences matters more than ever in our interconnected age.

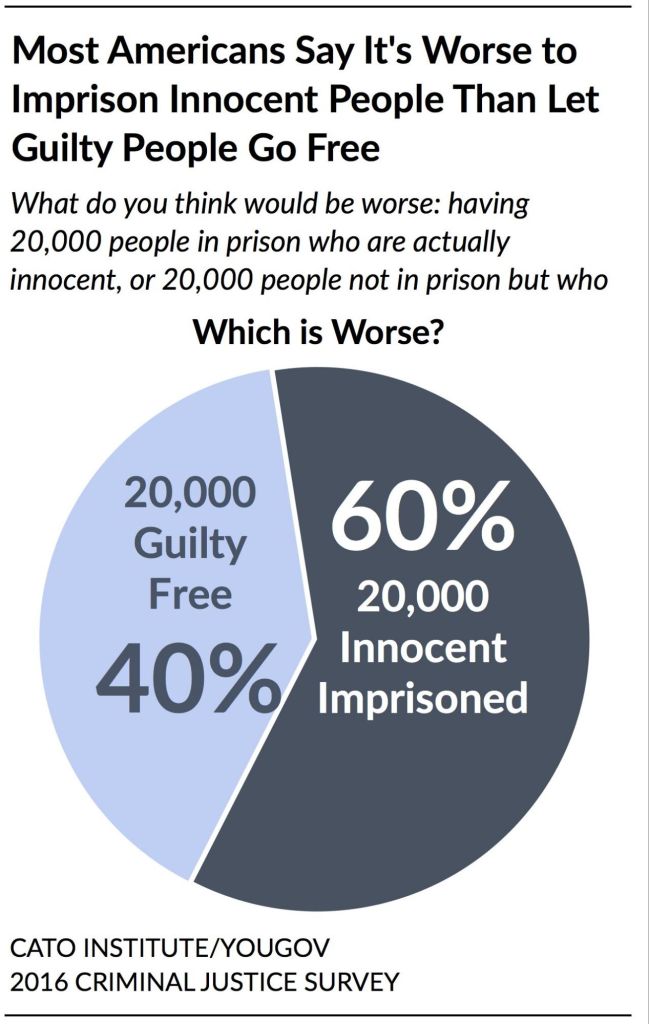

Innocent Until Proven Guilty and the Blackstone Ratio

Wrongful convictions happen. We often assume, since someone was charged, that they must be guilty of something. I mean, why else would they be wearing that orange jumpsuit? But this impulse goes contrary to reality where cops plant evidence, people lie, and prejudice plays a role in judgment.

This was the case with Brian Banks—who had been accused of rape by a classmate who later, after his years in prison, confessed to fabricating the whole account. What a horrible predicament: your whole future blown up, a jury that only sees your guilt.

A jurist, Sir William Blackstone, understanding the imperfection of the justice system and that the ultimate goal of justice is to protect the innocent, proposed:

It is better that ten guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer

This, the Blackstone ratio, is foundational to how things are at least supposed to work in the United States. Founding father Ben Franklin actually took the concept further by stating, “it is better 100 guilty Persons should escape than that one innocent Person should suffer.” John Adams, while he defended the British soldiers charged with murder for their role in the Boston Massacre, argued the following:

We find, in the rules laid down by the greatest English Judges, who have been the brightest of mankind; We are to look upon it as more beneficial, that many guilty persons should escape unpunished, than one innocent person should suffer. The reason is, because it’s of more importance to community, that innocence should be protected, than it is, that guilt should be punished; for guilt and crimes are so frequent in the world, that all of them cannot be punished; and many times they happen in such a manner, that it is not of much consequence to the public, whether they are punished or not. But when innocence itself is brought to the bar and condemned, especially to die, the subject will exclaim, it is immaterial to me, whether I behave well or ill; for virtue itself is no security. And if such a sentiment as this should take place in the mind of the subject, there would be an end to all security whatsoever.

This commitment to the innocent reflects a strong emphasis on individual rights. It also seems rooted in the story most defining of Western religion, and that is the story of Jesus—falsely accused and put to death for the sake of political expediency. This has become the defining narrative and a reason to reflect on our judgment rather than react. It is why many principled conservatives are always uncomfortable with those trials in the court of public opinion where the state parades a prosecuted person and people assume this is proof of an airtight case.

Tyler Robinson currently stands accused of murdering Charlie Kirk. Some have decided his guilt to the extent of forgiving him prior to his even standing trial or being given the chance to defend himself—as if there’s just no way that anyone other than him could be involved. That’s not justice; that’s denying him a presumption of innocence and might be enabling others to escape accountability for their involvement. It is better that he go free than chance a wrongful conviction—that is just Christian.

Caiaphas’s Expediency Math: Killing One to Save All

At the completely opposite end of the spectrum from the Christian West is the example of the high priest who claimed the murder of an innocent man was necessary to save Israel from destruction:

Then one of them, named Caiaphas, who was high priest that year, spoke up, “You know nothing at all! You do not realize that it is better for you that one man die for the people than that the whole nation perish.”

(John 11:49-50 NIV)

This may very well be the origin point of trolley problem moral reasoning, where a hypothetical situation is proposed in which an intervention will cost fewer lives. If we just switch the track, this fictional trolley only kills one rather than multiple people. And it seems very reasonable. Isn’t it better when more people survive?

Caiaphas reasoned it was better to kill one Jesus to save Israel. But it didn’t work out that way. The entire nation—along with their temple and sacrificial system—was forever destroyed in 70 AD. The high priest’s moral reasoning was compromised and wrong. It did not save Israel to kill one man and may well have been part of what eventually led to the destruction of Jerusalem. Those who did not accept the way of Jesus continued, after his ministry ended, to kill his followers and resist their civil authorities. Had they taken one moment to reflect and reconsider their plan to kill their way to peace, they may have survived intact rather than be spread to the corners of the empire.

The problem with killing one—without a just cause, to secure the future—is that it usually doesn’t end there. Kill one and you’ll kill ten; if you kill ten, you’ll kill 100, until soon it is millions upon millions. We see this in the campaign against Gaza. Tens of thousands of children are slaughtered and this is being justified as a war against terror. The reality is that it may very well create the backlash that will make the Zionist project untenable as people see this notion of blood guilt and collective punishment as repulsive. This is not compatible with the Christian values of the West and will lead to our destruction if the escalation of war is not rejected.

The world is better when we don’t play God and use the expediency math. If you’re okay killing one innocent person, you’re now an enemy of all humanity. And if you are willing to kill one, then the second and third come much easier. Innocent life should always be protected—whether it is the life of Jesus, be it the “enemies'” children, or the unborn. Pro-life means no excuses for the IDF that don’t equally apply to Hamas. If it is okay for the Zionist regime to kill scores of civilians as “collateral damage” for every militant killed—where even the Israelis admit the victims of their onslaught are 83% civilians—why mourn when it is just a handful in Bondi?

The best protection of innocent people, like your own, is to oppose all killing of innocent people no matter the color of their skin or the clothes they wear. If the IDF can kill a journalist claiming they are “Hamas with a camera” or “Hamas-affiliated,” then why is it wrong for Eli Schlanger, who has materially aided a genocide, to be targeted along with his associates? We need to reject this math of expediency no matter who is using it, or we can’t be upset when what goes around finally comes around.

Abraham’s Plea for Mercy: Sparing the Many for the Few Righteous

Now we can go way back, to the book of Genesis, where the world’s most powerful monotheistic religions find their foundation, and this man of faith named Abraham. We join him prior to the destruction of Sodom and have this interesting exchange:

Then the Lord said, “Shall I hide from Abraham what I am about to do? Abraham will surely become a great and powerful nation, and all nations on earth will be blessed through him. For I have chosen him, so that he will direct his children and his household after him to keep the way of the Lord by doing what is right and just, so that the Lord will bring about for Abraham what he has promised him.” Then the Lord said, “The outcry against Sodom and Gomorrah is so great and their sin so grievous that I will go down and see if what they have done is as bad as the outcry that has reached me. If not, I will know.” The men turned away and went toward Sodom, but Abraham remained standing before the Lord. Then Abraham approached him and said: “Will you sweep away the righteous with the wicked?

(Genesis 18:17-23 NIV)

Abraham’s opening question, in the passage above, tells you a whole lot about his moral reasoning. But before that you basically have the old covenant explained in brief: The blessing that was being bestowed on Abraham had to do with “doing what is right and just” or not simply being a blood relative of him, which is something that Jesus and the Apostles explained over and over to those who saw their genetic tie to the patriarch as a sort of entitlement and did not act justly or mercifully as he did.

Continuing in the text, take time to contrast the expediency math of Caiaphas with the following:

What if there are fifty righteous people in the city? Will you really sweep it away and not spare the place for the sake of the fifty righteous people in it? Far be it from you to do such a thing—to kill the righteous with the wicked, treating the righteous and the wicked alike. Far be it from you! Will not the Judge of all the earth do right?” The Lord said, “If I find fifty righteous people in the city of Sodom, I will spare the whole place for their sake.” Then Abraham spoke up again: “Now that I have been so bold as to speak to the Lord, though I am nothing but dust and ashes, what if the number of the righteous is five less than fifty? Will you destroy the whole city for lack of five people?” “If I find forty-five there,” he said, “I will not destroy it.” Once again he spoke to him, “What if only forty are found there?” He said, “For the sake of forty, I will not do it.” Then he said, “May the Lord not be angry, but let me speak. What if only thirty can be found there?” He answered, “I will not do it if I find thirty there.” Abraham said, “Now that I have been so bold as to speak to the Lord, what if only twenty can be found there?” He said, “For the sake of twenty, I will not destroy it.” Then he said, “May the Lord not be angry, but let me speak just once more. What if only ten can be found there?” He answered, “For the sake of ten, I will not destroy it.” When the Lord had finished speaking with Abraham, he left, and Abraham returned home.

(Genesis 18:24-33 NIV)

Abraham, after expressing his concern for the innocent, offers an opening bid at fifty righteous. Will God spare the entire wicked city for just fifty? And the first thing that is obvious is his humility, pleading with “I am nothing but dust and ashes” and showing his attitude before God. Second is that his orientation is toward the sparing of innocent life even if it means the evil people of the city of Sodom escape deserved judgment. This is in line with Blackstone’s ratio and in total opposition to Caiaphas, who argued to sacrifice rather than to protect the righteous one. Eventually Abraham concedes, and it makes more sense just to evacuate those righteous—nevertheless the righteous are not destroyed with the wicked.

So why is this account in Genesis?

Why is God engaged in a negotiation with a mere man?

The answer is that this anecdote is here for a reason, and that is to be instructive. The author of Genesis isn’t just telling us that Abraham was righteous—they’re giving us instruction on how to be righteous. To have the same disposition as Abraham, that’s the way to be a child of Abraham, and the path of righteousness that leads to the blessings through God’s promise. Chosen means you believe and obey the Lord. You can’t claim to be children of God, or of Abraham, if you truly share nothing in common with them in terms of your behavior or spirit. Genesis is telling us what that looks like in practice.

Christian Orientation Towards Mercy and Humanity is Truly Abrahamic.

In traversing these three moments—from courtrooms shaped by Christian reflection on an innocent’s crucifixion, to the high priest’s fateful expediency that failed to save his nation, and back to Abraham’s humble plea for mercy amid judgment—we uncover a profound reality: The orientation of the Christian perspective, underpinning American rights, is directly the opposite of the ideological lineage of Caiaphas.

The commitment, in faith, to protecting that one innocent life in a crowd of evil is to be a son or daughter of Abraham. Those who do the opposite, who are willing to sacrifice the innocent for sake of expediency, carry none of the character of Abraham and cannot be the heirs of anything promised to him. They must first repent of their sin—then they can be blessed, with all nations, through the one singular seed of Abraham (Gal 3:16) which is Christ Jesus.

Going back to the start and those ethics ingrained in us through a religiously derived culture and our assumptions, those who have rejected Christ and are completely willing to kill innocent people to accomplish ends are also going to manifest the other evil traits of Proverbs 6:16-19:

There are six things the Lord hates, seven that are detestable to him: haughty eyes, a lying tongue, hands that shed innocent blood, a heart that devises wicked schemes, feet that are quick to rush into evil, a false witness who pours out lies and a person who stirs up conflict in the community.

Those of us raised in an Anabaptist church got a strong dose of the Gospel according to Matthew and were taught that speech should be simple and truthful. Let your yea be yes, and nay be nay is about truly honest conversation and credibility without relying on oaths. We were told to have a peaceable spirit and merciful approach with all people—to be humble.

This is an orientation that many of Christian faith may believe is universal. Except it is not. Ethno-supremacist pride is okay with those of certain ideologies, deception for sake of gaining an upper hand is looked at like a virtue, they look at their ability to trick you as proof they are superior, and sow the seeds of division covertly not to be caught—like this example:

In a covert operation during 2007–2008, Israeli Mossad agents impersonated CIA officers—using forged U.S. passports, American currency, and CIA credentials—to recruit members of the Pakistan-based Sunni militant group Jundallah for attacks inside Iran, including bombings and assassinations targeting Iranian officials and civilians, as part of a broader effort to destabilize Tehran’s regime amid nuclear tensions. The deception, conducted openly in places like London, aimed to frame the United States as the sponsor, exploiting Jundallah’s sectarian and separatist motives while providing plausible deniability for Israel; U.S. officials uncovered the ruse through internal investigations debunking earlier media reports of CIA involvement, leading to outrage in the Bush White House (with President Bush reportedly “going ballistic”), strained intelligence cooperation under Obama, and the eventual U.S. terrorist designation of Jundallah in 2010, though no public repercussions were imposed on Israel.

(Overview above by Grok, read: False Flag)

Imagine having a friend who deliberately set you up for a fight against another person by telling them that you said something about them. My son had a bully do this to him on the bus and this is exactly what so-called ‘greatest ally’ tried to do to the US. For the Zionist regime, and Mossad, conducting the terror operation via a Pakistani proxy simply was not enough. They wanted Iran to think the attacks originated with the US in order to provoke a reaction. And this is how the world becomes a cesspool, all because the Iranians won’t stand idle while Palestinians are deprived of land and human rights.

Deviousness is not exclusive to the children of Caiaphas. But there’s no stops for those willing to kill innocent people for the sake of expediency. And a partnership with them is only going to undermine the foundation of our civilization. The US and ‘Christian’ West have already lost their moral reputation for this unholy alliance. We need to repent and return to holding evil men accountable and protecting the innocent or all will be lost—we can’t exempt some from a standard of normal decency without also damaging all of Christendom.