The dawn of artificial intelligence has led to much consternation about whether this is a good or bad development. But, in order to better understand the technology and the implications, we must first define what we mean by intelligence. What does it mean to be intelligent? What makes us intelligent beings?

The definition of intelligence, provided by Google, is “the ability to acquire and apply knowledge and skills.” But this seems to be a little vague and inadequate. Robots, used in manufacturing, already apply knowledge and skills—things programmed into them by human operators. And “ability to acquire” isn’t too clear either. So we need to break this down further.

Intelligence is the ability to usefully process information.

It has components.

First there is the ability to interface within a broader space or an external environment. If there is no information to input them there is nothing to intelligently process. Our senses are what connects us to the physical world and part of how we navigate through life. An internal model of the outside domain starts with information gathering or interface.

Second, intelligence requires memory, the capacity to remember past success and failures. Much of what counts as human intelligence is a bunch of procedures and formulas we obtained from others through language. This rote learning isn’t actually intelligence, memory or knowledge alone aren’t intelligence, but it is definitely part of the foundation. Memory is one component of IQ we can exercise and expand.

Third, intelligence is an ability to recognize patterns, to accurately extrapolate beyond the data and draw the correct conclusions. The reality is that our ‘intelligence’ is mostly a process of trial and error, often spanning generations, which leads to advancement in technology and thought. All one needs to do is observe how major inventions came to be and the many flops along the way to realize we’re more like blind rats running through a maze, using impact with walls until we find an opening to pass through.

Forth, intelligence is an ability create good models to recombine existing ideas. Nikola Tesla was a genius and not only because of his knowledge. No, he could use what he knew to construct an apparatus in his brain, which he could then build in the real world. What set Tesla apart is that his imagination wasn’t fanciful. Indeed, anyone can proclaim that “there should be,” but it takes something else entirely to accurately extrapolate.

Finally, intelligence has an aim. Truly a pile of knowledge is worth much less than a pile of manure if it can’t be usefully applied. And if something is useful, that is to say that there is an underlying meaning or purpose. To be intelligent there must be some agency or will to drive it. Curiosity is one of the things that sets us apart, it moves us forward—questions like “what is beyond that mountain” or “how high does the sky go,” push innovation.

Intelligence is knowledge and abilities that are useful to something. Useful to us. And really becomes a question of what our own consciousness.

Intelligence Failure

“Primitive life is relatively common, but that intelligent life is very rare. Some say it has yet to appear on planet Earth.”

Steven Hawking

Another way to define what intelligence is is to explore what it is not. Encyclopedias hold knowledge, stored in human language, but a book on a shelf has no logos. It is the writer and reader that provide reason to the words, via their own interpretation or intended use, which is something that can’t be contained in ink on the page. There are many people who are full of knowledge, but it is largely trivial because they lack ability to put it to good use.

Another problem is perception. Even our physical eyes provide a very selective and distorted view of the world. We do not see everything and, in fact, can literally miss the gorilla in the room if our focus is occupied elsewhere. Many can’t comprehend their own limitations, they are guided through the evidence by confirmation bias and not with good analysis. We really can connect the dots any which way, see patterns in what is random truly noise, and errant perception is difficult to correct once entrenched.

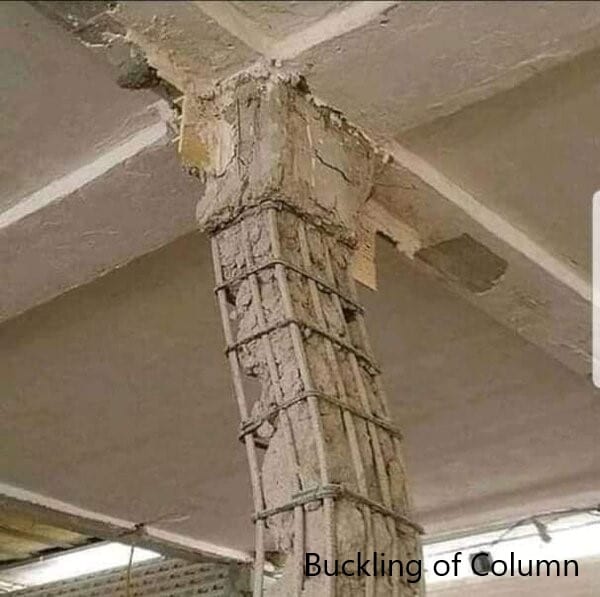

Intelligence must be about knowledge and theories that can be usefully applied. The intuitions we have that help us to navigate the mundane tasks do not necessarily help us to draw correct conclusions so far as the more abstract areas. People can persist in being wrong in matters that can’t be readily tested and falsified. Any processor is only as good as the data that is entered and the depth of the interpretative matrix through which it is sifted and measured. Even the slight error in one of the pillars of a thought, no matter how good the rest of the material is, can lead to an entirely failed structure.

Being slow is also a synonym for a lack of intelligence. That is to say, in order to be useful, information must be processed in a timely manner. Missing context and cues also leads to poor understanding, like Drax protesting the metaphor “goes over his head” with, “Nothing goes over my head. My reflexes are too fast. I would catch it.” It does not matter how much information you process if the conclusions are inaccurate or too late for the circumstances. Wittiness and a good sense of humor is a sign that a person is intelligent.

Intelligence is a continuum. We can have more or less of it. But measures like IQ don’t really mean that much, a person with a high IQ isn’t necessarily smart or wise. A Mensa membership doesn’t mean you’ll make good decisions or be free of crackpot ideas. Sure, it will probably help a person navigate academia and be more verbose in arguments, but it is not going to free someone of bias nor does it mean they’re rational. This is why true intelligence needs to be about useful application.

Deus Ex Machina

Deus ex machina, literally “god from the machine,” refers to a plot element where something arrives that solves a problem and allows the story to proceed.

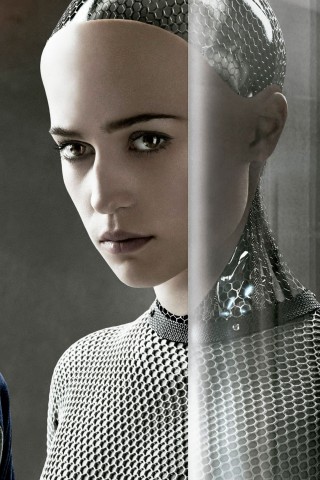

Ex Machina is also the title of a great movie which explores questions about artificial intelligence, with an android named Ava, her creator Nathan and a software engineer named Caleb. Caleb who was selected by Nathan is there to perform a Turing test and is eventually manipulated by Ava who uses his feelings for her as a means to escape. It is a sobering story about human vulnerability and the limits of our intelligence—Caleb’s human compassion (along with his sexual preferences) is exploited.

However, this kind of artificial intelligence does not exist. Yes, various chat bots are able to mimic human conversation. But this is not Ava talking to Caleb. There is not real self-awareness or observer behind the lines of code. It is, rather, a program that follows rules. Sure, it may be sophisticated enough to fool many people. But it is not sentient or being having agency, it is augmented human intelligence. They have essentially created a mannequin, not a man. Despite these bots being able to manufacture statements which sound like intelligence, they lack capacity for consciousness.

A true Ava would require more than mere ability to interact convincingly with humans, it would take the “ghost inside the machine,” that is to say duplicates our own singular experience of the present moment or has a mind’s I. This level of artificial intelligence doesn’t seem possible until we crack the code of our own self-awareness and that is a mystery yet to be solved. Even if you do not believe in things like immaterial spirit or detached soul, there is likely some special quality to the structure of our brains which creates this synthesis.

Without some kind of quantum leap, this A.I. technology will be an amplifier of the values of the creators, an intelligence built in their image and to serve them. It will not uncover objective truth or be a perfect moral arbiter. Nor will it be our undoing as a species. It will be a reflection of us and our own aims. It has no reason for it’s being apart from us. No consciousness, survival instinct or true being besides that of those utilizing it to extend their own.