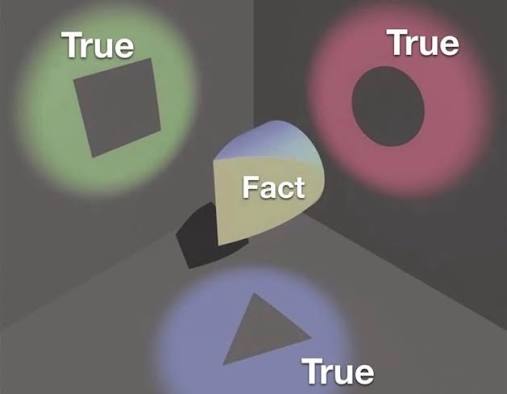

Everything we hear is an opinion, not a fact. Everything we see is a perspective, not the truth.

Marcus Aurelius

I will attempt to bring multiple threads together in this blog and the quote above is a good starting point. If there is objective reality it’s not going to be something possessed by one human. We do not know all circumstances nor can we vet and independently verify every fact we receive. Or at least not without becoming totally hamstrung by the details. We put our trust in parties, traditions, systems, credentials and the logic which makes sense to us.

The deeper we dive into our physical reality the murkier it all gets. The world ‘above’ that we encounter feels concrete. But there is not a whole lot of substance to be found as we get beneath the surface. The rules that we discovered—of time and space—end up dissolving into a sea of probabilities and paradoxes at a quantum level that we don’t have an answer to. And this is the ‘concrete’ observable reality. We all see our own unique perspective, a slice, and build our model of the world from it.

But it is even murkier when we get to topics of social science. Morality and ethics, built often from what we believe is fact or truth, is more simply opinion and perspective than it can be hammered out in words everyone is able to agree on. Even for those who are of the same foundational religious assumptions—despite even having the same source texts—do not agree on matters of interpretation or application. So who is right? And who is wrong? How do we decide?

1) Patrick: We Don’t Need God To Be Moral

My cousin, Patrick, a taller, better looking and more educated version of myself, an independent thinker, and has departed from his missionary upbringing—gives this great little presentation: “Where Do You Get Your Morality?“

His foundation for a moral value system is concepts of truth, freedom and love which he describes in the video. I find it to be compelling and compatible with my own basic views. Our cooperation is as natural as competition, it is what makes us human, and a conscience gives potential for better returns.

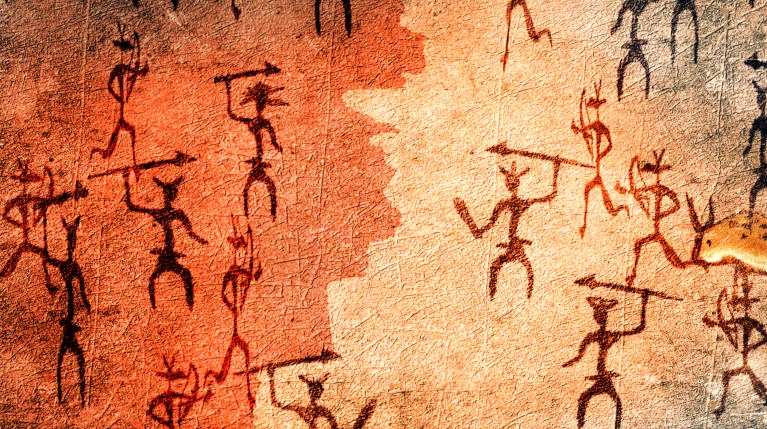

However, while I agree with his ideal, there is also reason why deception, tyranny and indifference are as common in the world—they are natural—and this is because it can give one person or tribe an advantage. Lies, scams, and political propaganda all exploit trust and can be a shortcut for gaining higher status or more access.

No, cheating doesn’t serve everyone. But the lion has no reason to regret taking down a slow gazelle. By removing the weak, sick, or injured, it inadvertently culls the less-fit genes from the herd, strengthening the prey population over time and even preventing overgrazing of the savannah. It’s just a raw service to ecosystem balance, much like a short seller who exposes those overvalued stocks, forcing the market corrections and greater efficiency—acts of pure self-interest yielding a broader good.

Herd cooperation or predator opportunism are different strategies, both 100% natural and amoral in their own context. I’m neither psychopath nor a cannibal, but I do suspect those who are those things would as readily rationalize their own drives and proclivities. Nature doesn’t come with a rulebook—only consequences.

I’m certainly not a fan of the “might makes right” way of thinking and that is because my morality and ethics originate from the perspective being disadvantaged. But I also understand why those who never struggled and who have the power to impose their own will without fear of facing any consequences often develop a different moral framework.

We need to be invested in the same moral and civilizational project. Or else logic, that works for only some who have the strength or propaganda tools, will rule by default. I don’t disagree with Patrick, but his core message caters to a high IQ and high empathy crowd—which does leave me wondering how we can bring everyone else on board?

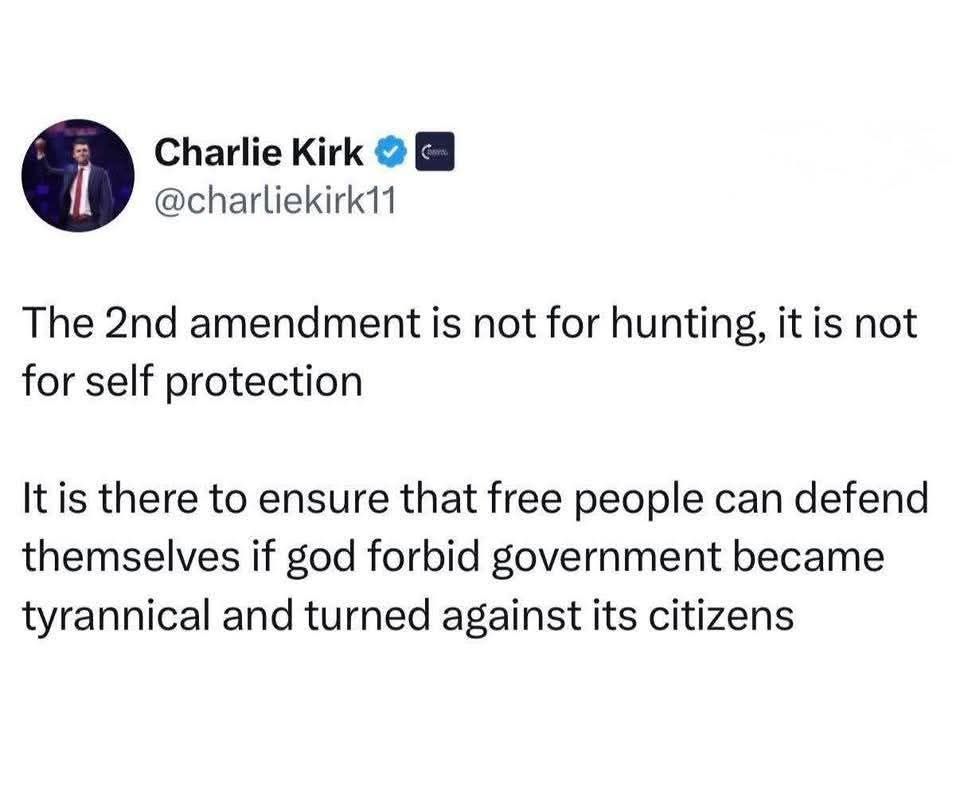

2) Kirk: A Way To Focus Our Moral Efforts

Charlie Kirk wasn’t a significant figure to me before his death. It may be a generational thing or just a general lack of interest in the whole conservative influencer crowd. I feel dumber any time I listen to Steven Crowder and assumed Kirk was just another one of the partisan bomb throwers. But, from my exposure to his content since, I have gained some appreciation.

Arguing for the Ten Commandments has never been a priority for me. It’s a list with a context and not standalone. Nevertheless it is a starting point for a moral discussion and also one that it seems Charlie Kirk would go to frequently in his campus debates. The two most difficult of these laws to explain to a religious skeptic are certainly the first two: “I am the Lord your God; Have no other gods before me and do not make idols.”

We generally agree on prohibition of murder and theft, or even adultery, but will disagree on one lawgiver and judge.

Why?

Well, it is simply because divine entity is abstract compared to things we have experienced—like the murder of a loved one or something being stolen from us. You just know this is wrong based on how it makes you feel. The belief in celestial being beyond human sight or comprehension just does not hit the same way as events we have observed. And it’s also the baggage the concept of a God carries in the current age. I mean, whose God?

It seems to be much easier just to agree the lowest common denominator: Don’t do bad things to other people.

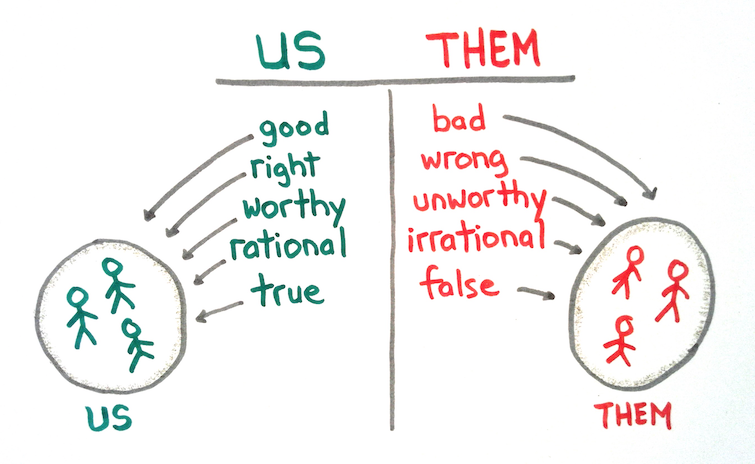

But then we don’t. We justify killing others if it suits our political agenda, labeling people as bad for doing what we would do if facing a similar threat to our rights. If I’ve learned one thing it is that people always find creative ways to justify themselves while condemning the other side for even fighting back against an act of aggression.

Self-proclaimed good people do very bad things to good people. Like most people see themselves as above average drivers (not mathematically possible), we tend to distort things in favor of ourselves. Fundamental attribution error means we excuse our own compromises as a result of circumstances while we assume an immutable character flaw when others violate us. We might be half decent at applying morality to others—but exempt ourselves and our own.

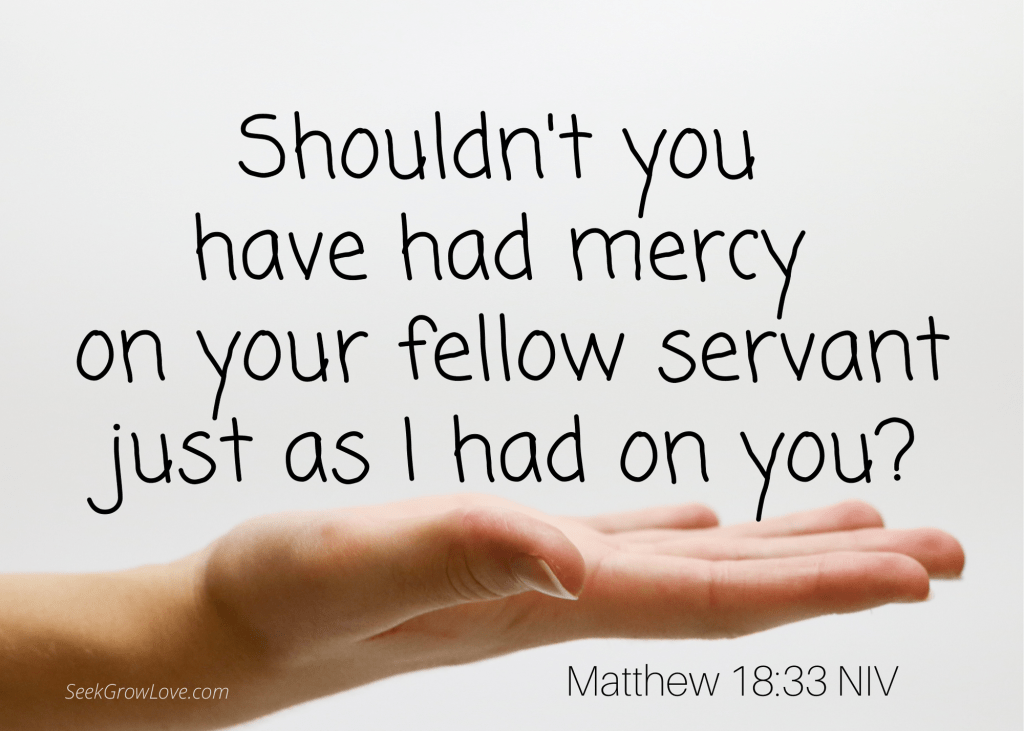

So morality needs a focal point beyond us as individuals. There must be a universal or common good. Which might be the value of a theoretical ‘other’ who observes from a detached and perfectly unprejudiced point, the ideal judge. Not as a placeholder, but as the ultimate aim of humanity. One God. One truth. One justice. This as the answer to double standards, selective outrage and partisan bias. If we’re all seeking the same thing there is greater potential of harmony and social cohesion where all benefit.

At very least it would be good to promote an idea of an ultimate consequence giver that can’t be bought or bribed.

3) The Good, the Bad and the Aim for What Is Practically Impossible

The devil is always in the details. And the whole point of government is to mediate in this regard. Unfortunately, government, like all institutions, is merely a tool and tools are only as good as the hands that are making a use of them. A hammer is usually used to build things, but can also be used to bash in a skull. Likewise, we can come up with that moral system and yet even the best formed legal code or enforcement mechanism can be twisted—definitions beaten into what the current ruling regime needs.

The United States of America started with a declaration including the words “all men are created equal” and a Constitution with that starts: “We the people…” This is reflection of the Christian rejection of favoritism and St. Paul telling the faithful “there is no Jew or Greek” or erasing the supremacy claims of some. An elite declaring themselves to be exempted or specially chosen by God is not compatible with this vision. We never ask a chicken for consent what we take the eggs. We do not extend rights to those who we consider to be inferior to us or less than human. Human rights hinge on respect for the other that transcends politics.

That’s where the labels come in. If we call someone a Nazi, illegal, MAGAt, leftist or a Goyim we are saying that they are less than human and don’t deserve rights. This is the tribal and identity politics baseline. Those in the out-group are excluded for decency, their deaths celebrated as justice (even if there’s no due process) and we’ll excuse or privilege our own. All sides of the partisan divide do this—we create a reason to deny rights to others often using things like truth, freedom and love (Patrick’s foundation) as our justification: “Those terrorists hate our freedom and democracy, we must fight for those we love and our truth!”

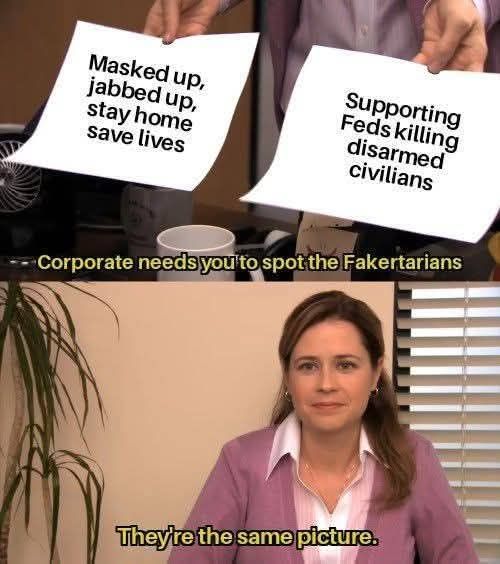

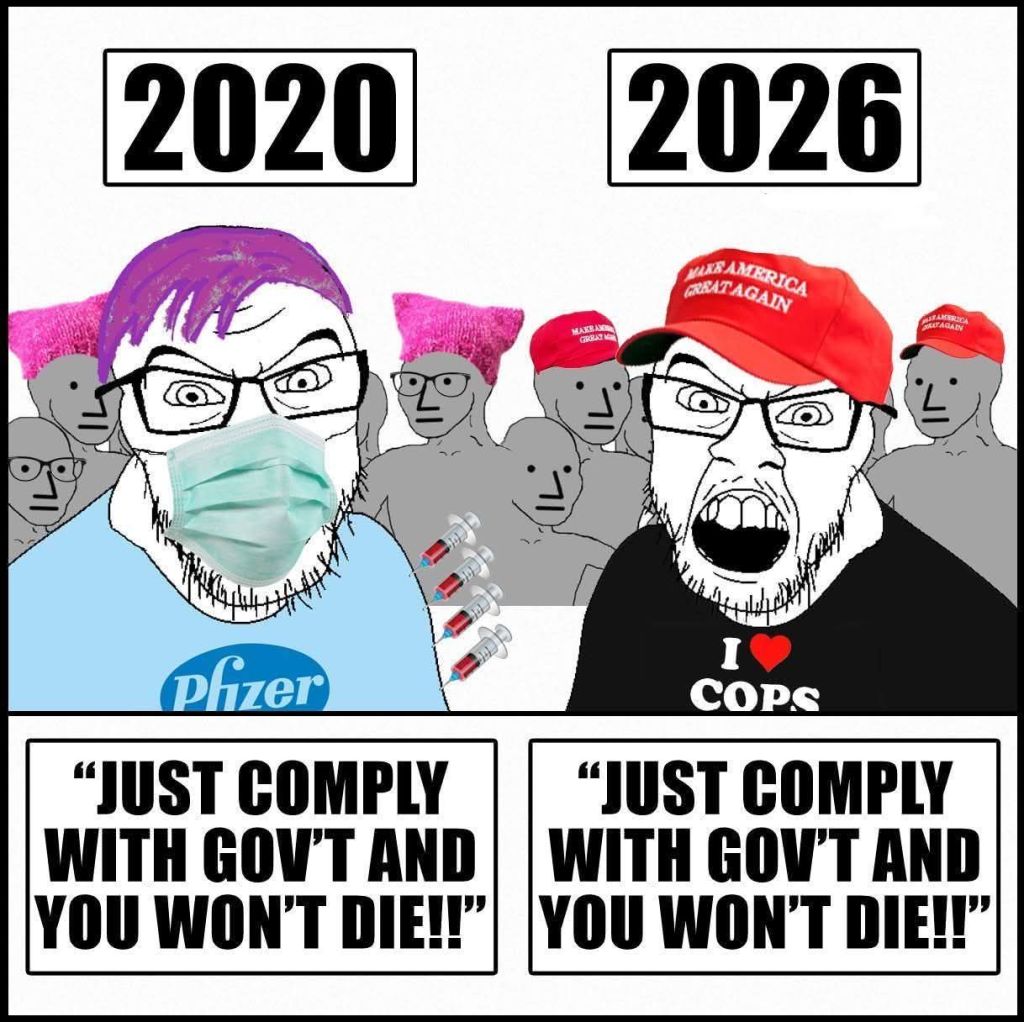

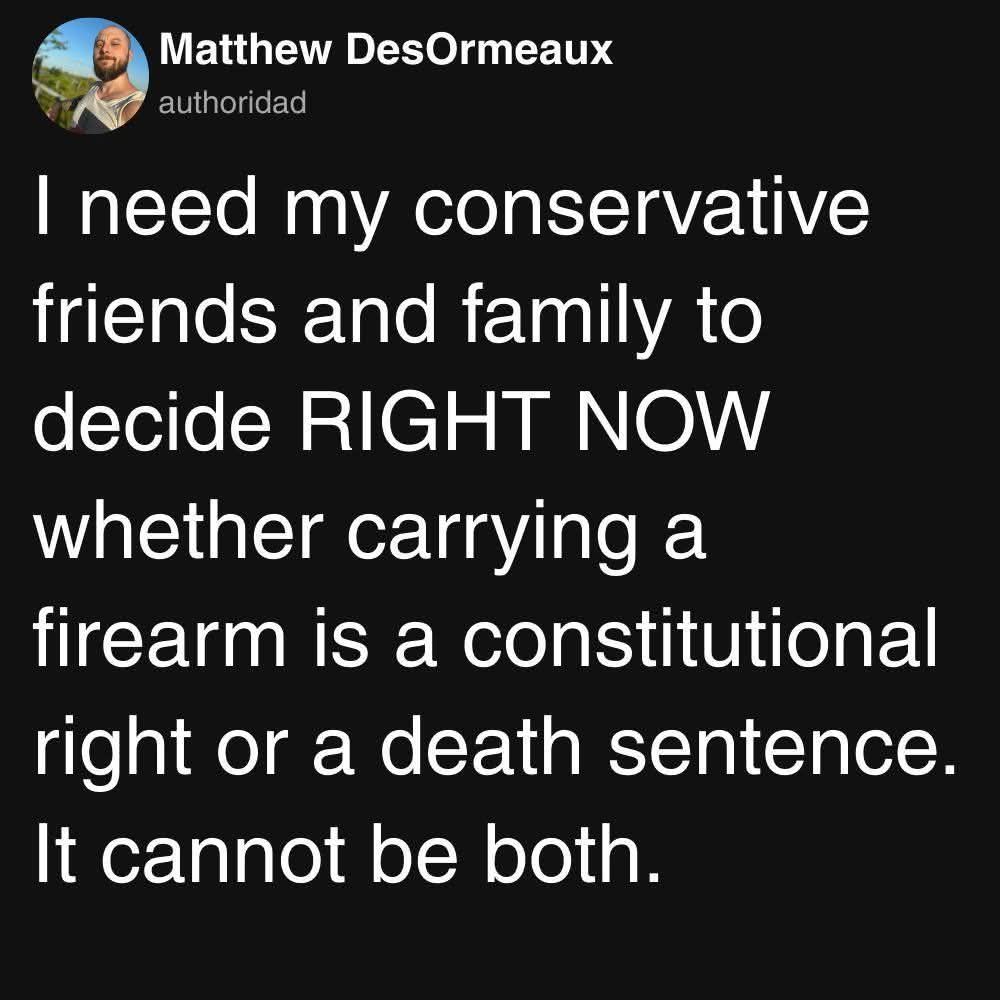

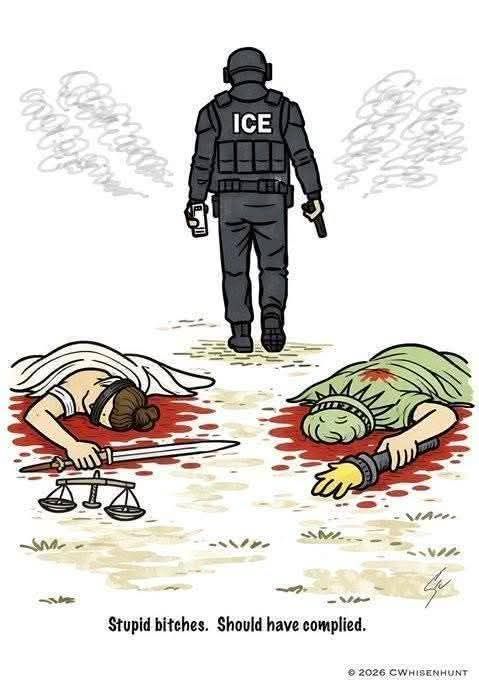

Bringing this to a practical level: Looking at Minneapolis, the ICE and anti-ICE activities, we have competing moral narratives and a different vision for application of American values. On one side of the debate you have those who say that “one is one too many” if an illegal immigrant kills a US citizen—then suddenly do not care when Federal agents shoot a fellow American. The defiant “don’t tread on me” opposition to mandates and masks during Covid somehow shifting to “comply or die!” On the other side you have those outraged about Kyle Rittenhouse and who have been traditionally opposed to the 2nd Amendment defending Alex Pretti while the Trump administration condemns a man for carrying a permitted firearm.

Judgment is for the other, it seems, rights for those who look like us or agree. It’s this inconsistent eye, the call for understanding of our own and grace for ourselves with the harsh penalties applied to those within the forever shifting lines of our out-group, that shows how our political perspectives cloud our moral judgment. The ‘sin’ is not the act itself, but whether or not the violation suits our broader agenda. This is why ‘Christian’ fundamentalists, who will preach the love of Jesus on Sunday, can be totally indifferent to the suffering of children with darker skin tones—their God is about national schemes not a universal good or a commonly applied moral standard.

The aim needs to be justice that is blind to who and only considers what was done. If pedophilia is excused for powerful people who run our government and economy, then it should be for those at the bottom as well. If the misdemeanor of crossing an invisible line is bad, a justification for suspension of due process for all Americans, then why is it okay to violate the sovereignty of Venezuela or Iran over claims of human rights abuse?

The US fought a war of independence, took the country for the British and yet has been acting as a dictator, installing kings, when it suits our neo-colonial elites.

That’s immoral.

We’re all immoral.

The moral code of Patrick, Charlie or myself is incomplete—because every moral code is incomplete when filtered through human eyes. We start from our different premises: Patrick’s secular triad of truth, freedom, and love; Kirk’s religious appeal to the Ten Commandments and a divine lawgiver as the only reliable check on self-deception; my own reluctant recognition that empathy and cooperation are real, yet fragile, against the raw arithmetic of power and advantage. Yet all of our approaches circle the same problem: without some external, impartial standard that transcends our biases, tribes, and self-justifications, our morality devolves into competing opinions dressed as facts—exactly as Aurelius observed.

We cannot fully escape the murk. Objective reality, if it exists, slips through our fingers like quantum probabilities—and moral truth fractures along lines of culture, experience, and interest. Even when we agree on broad principles (don’t murder, don’t steal), the application often splinters: whose life counts as being worthy of protection? Whose borders, laws, or children deserve a defense? And whose “justice” is merely revenge in better lighting?The temptation is cynicism—just declare all values relative, retreat to my own personal pragmatism, and then let might (or votes, or algorithms) sort the rest. But that is a path leads to the very outcomes we decry—dehumanization, selective outrage, and the erosion of the entire civilizational project that allows agnostic high-empathy and high-IQ arguments like Patrick’s to even exist. Yes, nature may be amoral, but us humans build societies by pretending otherwise, by our aiming higher than baser ‘animal’ instincts—reaching for God.

So perhaps the most honest conclusion is not to claim possession of the full truth, but to commit to pursuing it together—knowing we’ll never quite arrive. We definitely need focal points that force some accountability beyond ourselves: whether that’s a concept of one ultimate observer who sees without favoritism, or by a shared commitment to universal human dignity rooted in principle beyond biology or tribe, or simply just the hard-won habit of applying the same rules to our side as to the other. Blind justice isn’t natural or self-evident—it’s cultivated. Morality is an aim which requires vigilance against our own double standards, humility before the limits of our perspective, and courage to defend principles we claim even when they inconvenience us.

In the end, we don’t need perfect agreement on the source of morality to agree that inconsistency in application is poisonous. What goes around will certainly come around and if we live by the sword we’ll die by it. If we can at least hold each other (and ourselves) to a standard higher than “what works for my group right now,” preserve the space for mutually beneficial cooperation over cruel predation—a shared conscience over mere convenience. Anything less, and the gazelle never outruns the lion for long—and neither does the society which forgets why it tried.