We tend to lump things together that shouldn’t be. In other words, there is plenty of diversity within categories and this is something true of those whom we call mechanics. And the significant difference in mechanics is analogous to other professions, which is where this essay will end up.

The other week my old reliable Ford Focus began to act up. I had traveled, with my family, to a company picnic and everything was fine on the way out. However, on the trip home there was something that was not right. The power delivery was rough when trying to accelerate but smooth enough while cruising and immediately my mind went to the trick this 2.0 L had up its sleeve.

The ‘Duratec 20‘ has Mazda DNA. It uses direct injection and variable valve timing (or Ti-VCT) to make 160 hp while still delivering decent fuel mileage. With a 12.1:1 compression ratio, it has a decent torquey feel for a 4-banger, and—paired up with a five-speed—it is fast enough to be fun.

And to the point that a week prior to this, on the way to church, a late 90s Honda Civic with a loud pipe did the customary flyby, and we just so happened to line up at the next red light. So, as was necessary, to the slight embarrassment of my wife and great amusement of my son, I do the hard launch. It bogged a bit, despite my loading up a bit prior to releasing the clutch, so I dumped it down completely, the tires chirped, I hit second hard and I was grinning a couple of car lengths ahead before they knew what had happened. Not an actual race, but I’m pretty sure I had the edge even if they were ready for me.

The engine light would eventually come on in the next day or two. And, sure enough, checking the code at AutoZone, it came up as a camshaft sensor. That was something I could handle. I swapped in the new part. But it didn’t fix the problem. I noticed that the negative battery terminal had some corrosion and, with the help of a cousin, we cleaned that. Still, no dice. The issue persisted.

Shop #1: The Inspection Garage

With the help of a mechanic friend of mine, who sent me the applicable page of the diagnostics manual, I determined that the problem was now beyond my shadetree abilities. It was potentially a crank sensor fault (that for some reason shows up as being the cam sensor) or involved some sort of wiring issue. I took it to the garage, within walking distance, which had given me a better deal for vehicle inspection than the dealer could offer.

I left them with the page of the manual. I returned to a vehicle with a drained battery and still acting up despite their efforts. They had cleaned the throttle body, changed the air filter, and not overcharged me for that service. However, the problem was not fixed, and the explanation he gave—that the car (with over 230,000 miles) was old and probably down on compression—did not satisfy me.

I had assumed that they had run down the diagnostics checklist, as I had basically told them to do, and that weekend decided to take a look again with the aid of a mechanically inclined brother-in-law at our family summer get-together. My sister has a 2016 Focus, which had corrected the wiring harness issue, and immediately, while looking at her engine bay, I noticed how the Ford had moved these wires from where they were on my own 2014.

So I took another look at that, I lifted the harness on my car where it was against the engine and, sure enough, I could see the cover was worn through and a little copper was shining. Uh-oh. With a small piece of electrical tape and a spirited tested drive, the diagnosis was clear—that was the problem and I would need to take it to a shop that was capable of following my instructions.

Shop #2: The Technician

After pricing my options, I decided on a garage that had helped me with another mystery issue years ago with my Jaguar XJR. Jake, the owner, was an expert at diagnostics and, in a conversation with Jason who he trained as his replacement, it was clear that this guy knew his stuff. Now, granted, in this case, I had already provided the diagnosis. However, I could tell that he understood the systems of the vehicle far better than the guy at the inspection garage.

This is the kind of mechanic you need when the issue is more than an alternator or something obvious that only needs to be removed and replaced. Anyone can turn a wrench. Quite a few can go down the diagnostics checklist and eventually find the solution. But the actual technician type is a different breed, he is the guy who writes the manual and can even feel what is going on after a short test drive. These are the Ken Miles, can-improve-what-already-is kind, who in different circumstances may have become an engineer or even a doctor.

The technicians are professionals. They have a high IQ and a wealth of knowledge. And it is about much more than having the correct certifications or a toolbox full of Snap-On tools. Some simply do not have the aptitude even if they went through years of training and others do. The technician could be working in the back alley of Manila or at the dealership down the road. There are different levels even within this group, but what sets them apart is their intuitions and ability to model the complex systems of a vehicle in their heads. He’s as smart as your cardiologist.

Shop #3: The Scam Artist

Years ago my brother took his Ford Tempo in for a routine inspection. This was his first car and basic transportation for a teenager. And only cost a few thousand dollars, which was basically all he could afford at the time. The tire shop is in the middle of town and looks decently professional. I think of this incident each time I see their advertising two decades later.

The bill he got was more than the value of the car. Apparently, they decided that every suspension part was out of tolerance and maybe they were technically correct, who knows?

What I do know is that my dad took severe issue with this and helped my brother negotiate a slightly better price for the work. Still, they soaked him for a huge amount of money and have lost our business since then. They were at the level of the inspection shop, or your local Walmart Auto Care Center, as far as their abilities and yet telling us with absolute conviction that the car was not safe to drive without the laundry list of parts with labor they installed without so much as a phone call to my brother.

Dealerships can overcharge. But usually, they are more reputable and not just replacing parts because they have you over the barrel and have a bonus to make. These are the types who would convince your grandma she needs the blinker fluid filled and muffler bearings replaced. They aren’t technicians (they would too be ashamed of themselves if they were) and are basically just swindlers with a wretch to use as part of the scheme. Their diagnosis is always something expensive.

What Kind Of ‘Mechanic’ Is Your Doctor?

This understanding of different types of mechanics applies to all professions. Not every college graduate with the right credentials is equally qualified. Some engineers are really good at the classroom stuff, they know the code and can be completely anal about largely irrelevant or unimportant details. Others really get what makes structure work, it is intuitive to them, and what they build is likely safer than the variety that dots all of the I’s and crosses all the T’s according to the IBC 2021.

Doctors come in many varieties as well. There are those types who get into things like cosmetics or reconstructive surgeries, chasing after the big bucks, and then there are the others who want to run a clinic or set up a family practice to help as many people as possible. The country ‘doc’ driving the F-150 is a different breed than the one with a BMW or Porsche. One is practicing medicine, and the other has a profitable business that requires some medical skills. And, in both cases, competency is not strictly a matter of gathering the right diploma or getting through the board requirements.

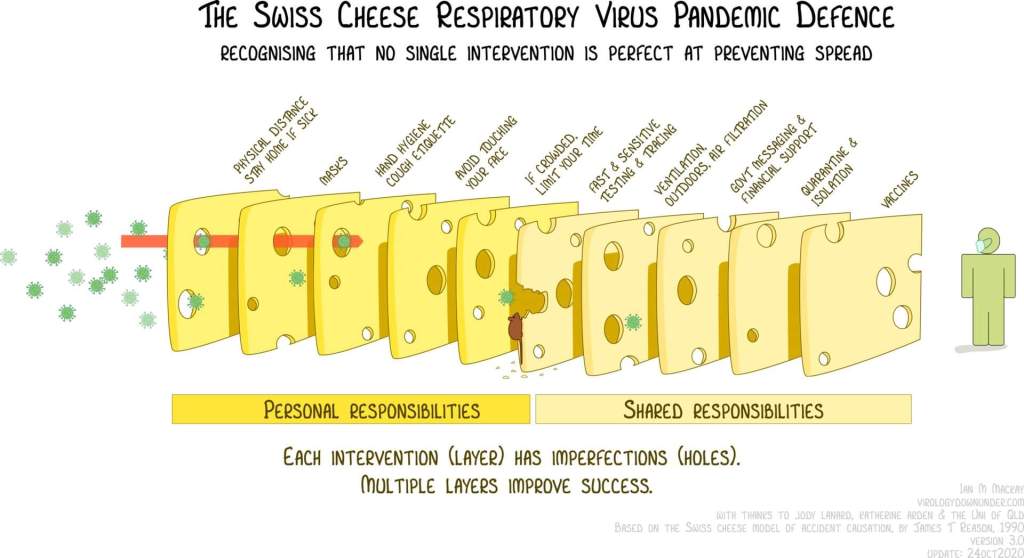

My own hunch is that most doctors are more like the inspection shop mechanic. They’re not out to screw you over and they also do good work for the most part. However, they got where they did because they were at least of slightly average intelligence and good at navigating the system. This doesn’t mean that they are actually doing the real number crunching of the diagnostics themselves. No, it means that they can match a list of symptoms with what they can find in the Merck manual and write a (barely legible) prescription. This could mean that they miss things, over-prescribe, or basically share in the same failures as the entire medical establishment.

So, how reliable is the system?

Well, I’m not sure.

When I read things like, Why Most Published Research Findings Are False, and how the Lancet published (then later retracted) studies that cautioned against the use of Hydroxychloroquine or how Ivermectin was skewered as being “horse dewormer” despite being an effective anti-viral medication, it seems that politics may be dictating the science. And we all know that politics is heavily influenced by cold hard cash. So, let’s think, who benefits from keeping these kinds of cheap widely available therapeutics from the market? There was an industry that made $90 billion from the pandemic and also has connections to the corporate media apparatus. Who knows how far this big money penetrates government agencies and impacts regulations or policies.

But I do know this has been said…

“It is simply no longer possible to believe much of the clinical research that is published, or to rely on the judgment of trusted physicians or authoritative medical guidelines. I take no pleasure in this conclusion, which I reached slowly and reluctantly over my two decades as editor of The New England Journal of Medicine”

Marcia Angell, MD

And this…

“The case against science is straightforward: much of the scientific literature, perhaps half, may simply be untrue. Afflicted by studies with small sample sizes, tiny effects, invalid exploratory analyses, and flagrant conflicts of interest, together with an obsession for pursuing fashionable trends of dubious importance, science has taken a turn towards darkness”

Richard Horton, editor of The Lancet

I’m assuming these two would know a little about the current state of science and medicine.

So how does a doctor separate the wheat from the chaff?

It is not right that some see the failures of some as a reason to dismiss it all. Getting taken advantage of by one repair shop doesn’t make all mechanics crooks. Still, how does a patient know if their doctor is doing a high-level analysis of the evidence, is capable of critical thinking and going beyond the book, or if he’s just following the pack without doing any truly independent diagnostics? It really takes someone a bit removed from the profession, who doesn’t share their biases or bad remedies, to give the corrective treatment. Maybe a car mechanic turned doctor (the guy in the featured picture) would have some useful perspective on the topic?

Whatever the case, if we can’t trust everyone who is licensed by the state to inspect vehicles, we should be even more skeptical of those who want to put things into our bodies. They don’t even have to be bad or intend harm, it could simply be that they are asleep at the wheel, putting trust in institutions that have been compromised and corrupted. At the very least, the body is extremely complicated and even our most advanced methods are crude. We may not know that our modern versions of bloodletting are of negligible value or even harmful for another century or two. This is why we customers, the patients, should never be pressured one way or another even if the science is supposedly settled.

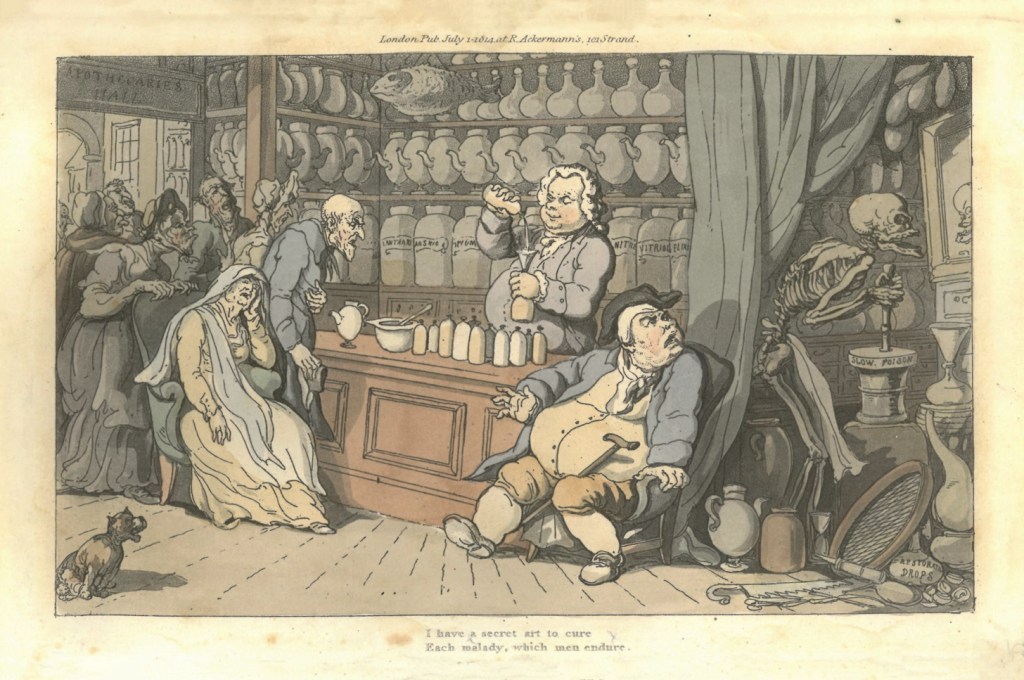

Yes, even those at the top of the profession today may be tomorrow’s quacks…

Note the “slow poison” written on the mixing device.