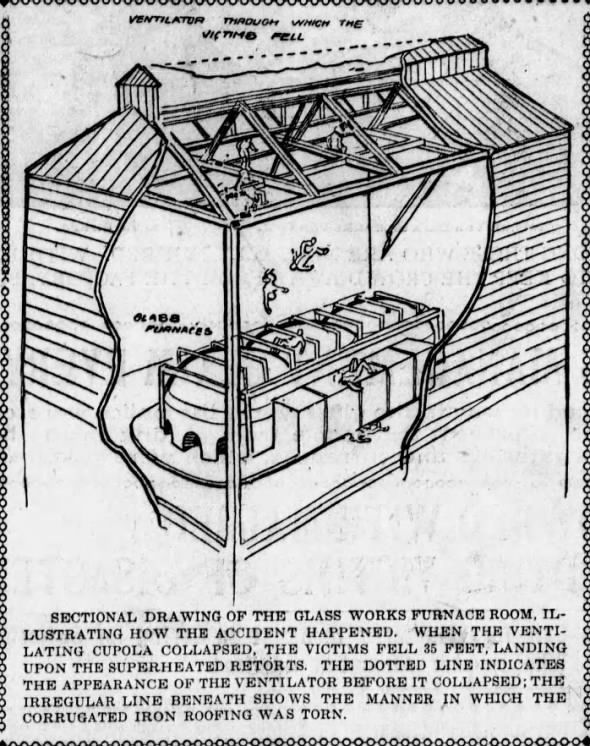

It was November 29, 1900, and fans filled the stadium in San Francisco for the annual Thanksgiving Day game between California Golden Bears and Stanford Cardinal. Some, not wanting to pay the entry fee (one dollar then, $40 in today’s money), climbed on a nearby glass factory roof to get their view of the action on the field.

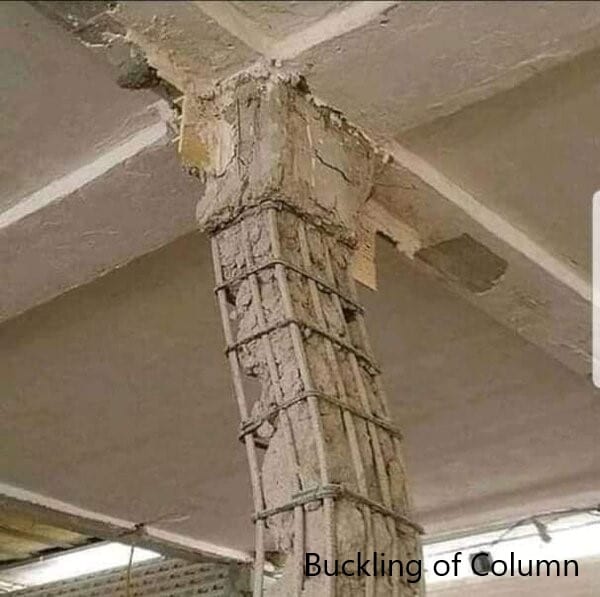

The newly built factory roof collapsed about twenty minutes into the game. One hundred people fell as it gave way and plunged four stories down—many landing on the 500° F oven below. It was a horrific scene. Young people being cooked alive. What happened? The building roof wasn’t designed to hold a mass of spectators. It failed. Those who had climbed up were oblivious or did not have enough concern for the stress they were adding to the structure.

This tragedy wasn’t just a failure of design; it revealed a deeper misconception that buildings should be invincible, a myth that shapes our reactions to collapses even today. It goes further than engineering or physical buildings as well. Our models of reality are oversimplified at best and flat-out wrong in too many cases.

There is a common misconception and an unrealistic expectation about structures—many people seem to assume they are like blocks of granite. From those who believe that every building collapse is a conspiracy to those who think every failure demands stricter government regulations, the myth of an indestructible building continues due to a lack of understanding of engineering and the limitations.

Design Limits Are Not Defects

One key misunderstanding is design limits. Engineering is not about making a building too strong to ever fail. Unless we’re talking about the Great Pyramids, it’s all about trying to meet certain established parameters. An engineered building is designed to meet the expected conditions as defined by regional building codes. If the wind, snow, or loads exceed the designated standards, then there will likely be a collapse.

Earlier this year, after a heavy snowfall in upstate New York, many buildings had their roofs cave in (including this fire hall) because the weight of the snow was that much greater than the design weight. Sure, most engineers build an extra safety margin into their components, but eventually these limits are too far exceeded and you’ll end up with a tangled mess. This is why there are sideline roof shoveling businesses in these places where large snow accumulations are a regular occurrence.

Sure, code could force people to build to a much higher standard, making a collapse due to snow load virtually impossible. But this would increase the costs so much that it would price many people out of building a new house or barn. Engineering is all about compromise, more precisely about making the right compromises given the expected conditions. Yes, there is a case for making adjustments based on observation or after studies, but ultimately we build for what will work most of the time.

More Is Not Always Better

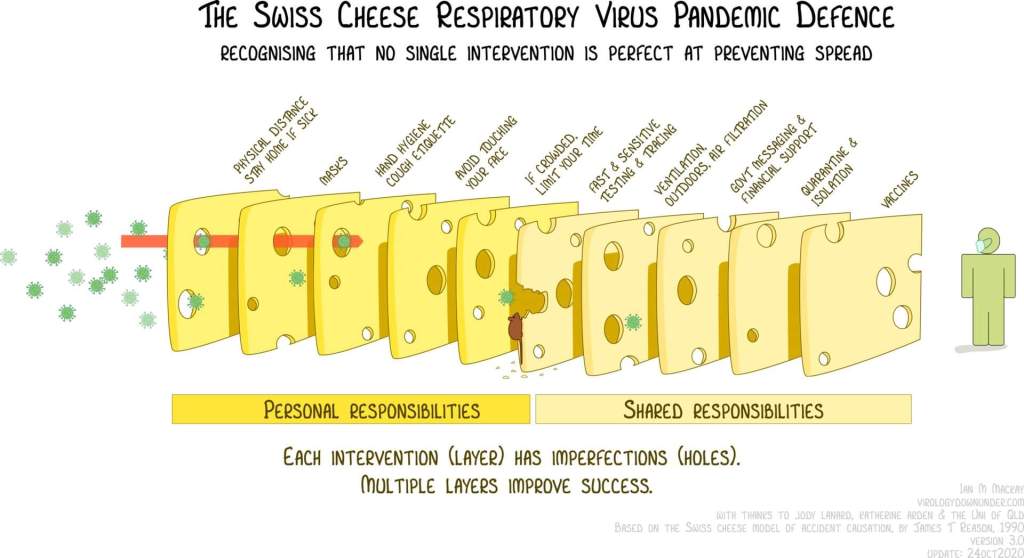

In the aftermath of the earthquake that had struck Myanmar and neighboring Thailand, there was a comment made to me in a chat hoping for more layers of regulation. This is a sentiment, in the specific context of rapid development of Bangkok, that seems more reflexive than reflective. It is a progressive impulse to believe that more interventions and rules are the answer.

But, for me, as someone who works in the construction industry and has occasionally needed to sift through these layers, I could not disagree more. Sure, better regulations may be needed. However, legalism doesn’t work in building standards any better than it does in churches. Sure, you need a code of some kind. And yet onerous regulation will add to the cost of construction, not necessarily improving the end results, and only making new housing less accessible.

It is, at best, the same trade-off discussion we can have about self-driving cars and the need for LIDAR. Sure, this expensive laser ranging system may marginally improve the results, but at what cost? Self-driving cars with cameras alone are already safer than human drivers. Keeping these systems at a price that is affordable will save more lives than pricing them out of reach for average people. It is, therefore, optimal to rollout the less expensive and safer tech even if it could be slightly improved.

At worst there is only more expense and no benefit to more layers of red tape. The real problem with rules is that they are written in language that needs interpretation. Unlike a classroom theoretical setting, in the real world you can’t just memorize the correct answers and pass the test. The ability to make a judgment call is far more important than adding to the pile of regulations. More rules can mean the more confusion and the truly critical matters get lost in the mess.

I see it over and over again, when different customers send the same job for a quote and all of them interpreting the engineering specifications their own way. It is the tire swing cartoon, a funny illustration of when the customer wants something simple and yet the whole process distorts the basic concept until it is unrecognizable. That is where my mind goes when we talk about adding layers. Is it increasing our safety or merely adding more points of failure?

Some of it is just that some people are plain better at their jobs than others with the very same credentials. I am impressed by some engineers, architects, contractors, and code officers—not so much by others. I’m willing to bet the intuition of some Amish builders is probably more trustworthy than a team of engineering students’ textbook knowledge, full of theory, with no real or practical world experience. In the end any system is only ever as good as the users.

Theory Is Not Reality

My work relies on truss design software. I enter information and it does those boring calculations. When I started, I assumed that it was more sophisticated than it really is. I thought every load was accounted for and nothing assumed. But very soon the limits of this tool started to reveal themselves. It is only as accurate or true to reality as the engineers and developers behind it—and on the abilities of the user (me) understanding the gaps in the program.

When it comes to mental models—the kind of physics involved in engineering—only a few people seem able to conceptualize the force vectors. Things like triangulation, or compression and tension loads, are simply something I get. Maybe from my years of being around construction or that curiosity I had, as a child, that made me want to learn what holds a stone arch up or why there are those cables running through that concrete bridge deck. My model was built off of this childhood of building Lincoln Log towers (arranging them vertically) and occasionally making mini earthquakes.

I’m exasperated by this expectation that people have for skyscrapers to be indestructible or to topple over in the same manner of a tree—as if they’re a solid object. It also seems that the big difference between static and dynamic loads is lost on most people. They don’t understand why a building could start to pancake, one floor smashing the next, or how twisting due to extreme heat could undermine the structural integrity of a building without ever melting the steel. Of course this has to do with their beliefs or mistrusts that are not related to engineering—nevertheless it shows their completely deficient understanding of how the science works.

The concept in their head is off, their brain modeling is inaccurate, and their resolution may be so low they simply can’t grasp what the reality is. You try to explain basic things and their eyes glaze over—sort of like when Pvt. John Bowers tried to explain why the plants need water, and not the electrolytes in Brawndo, in the movie Idiocracy. Ignorant people will scoff before they accept a view different from their model of the world. The theory they believe rules over all evidence or better explanation.

On the other side are those who trust every established system without understanding it. They “believe science” and see more as an answer to every question. More rules, a larger enforcement apparatus, faith in their experts, without any feel for the problems encountered by the professionals or those in the field. If they had, they would question much more than they do. Human judgment is still at the base of it all. Or at least that is what the lead engineer told me while we discussed the limits of software and the need to be smarter than the tool.

Not even AI can give us the right balance of efficiency in design versus safety factor or what should be written in the code. It may be a better reflection of our own collective intelligence than any individual, but our own limits to see the world how it actually is are not erased by the machines we create. We are amplified, never eliminated, by the tools we create. So we’ll be stuck wrestling with our myths and theories until we take a final breath—only our flaws are indestructible.

Models of a Messy World

If truss software taught me anything, it’s that no model nails reality perfectly—not beams, not buildings, not life. We lean on these frameworks anyway, because the world’s too wild to face without a map. But just like those fans on that San Francisco roof in 1900, we often climb onto flimsy assumptions, mistaking them for solid ground. The myth of an indestructible building is just one piece of a bigger distortion: we think our mental models—of faith, of power, of people—are unshakable truths, when they’re really sketches, some sharper than others, of a reality we’ll never fully pin down.

Take religion. For some, it’s a cathedral of certainty, every verse a load-bearing beam explaining why the world spins. Others see it as a rickety scaffold, patched together to dodge hard questions. Both are models—ways to grapple with life’s big “why.” Politics is messier still. It’s like designing a city where everyone’s got their own codebook. One side swears by tight regulations, convinced they’ll keep the streets safe. Another group demands open plans, betting that freedom builds stronger foundations. Both sides act like their own ideological model is bulletproof, shouting past each other while the ground shifts—economies wobble, climates change, and people clash.

Then there’s prejudice, the shoddiest model of all. It’s like sizing up a beam by its color instead of its strength. Prejudice, always a shortcut to save us from the effort of real thought, fails because it’s static, blind to the dynamic load of human individuals. Good perception, like good engineering, adjusts to what’s real, not what’s assumed.

All these—religion, politics, prejudice—come down to how we see. Perception’s the lens we grind to make sense of the blur. Some folks polish it daily, questioning what they’re fed. Others let it cloud over, stuck on a picture that feels safe but warps the view. I think of those fans in 1900, not asking if the roof could hold them. They didn’t mean harm—they just saw what they wanted: a free seat, a clear view. We do the same, building lives on models we don’t test, whether it’s a god we trust, a vote we cast, or a snap judgment we make. The distortion isn’t just in thinking buildings won’t fall—it’s in believing our way of seeing the world is indestructible.

What makes a model reliable? Not that it’s right—none are. It’s that it bends without breaking, learns from cracks, holds up when life piles on the weight. In construction, we double-check measurements because we know plans lie. In life, we’d do well to double-check our certainties—about the divine, the ballot, the stranger next door. The San Francisco collapse wasn’t just about a roof giving way; it was about people trusting a picture that didn’t match the world. We’re still climbing those roofs, chasing clear views on shaky frames. Maybe the only thing we can build to last is a habit of asking: what’s holding this up? And what happens when it falls?