Growing up, college sports, or even sports in general, were not part of my world. My father didn’t toss a football with me in the backyard or gather us around the TV for games—work was his recreation, and that was our normal. I had no reason to care. But something shifted later in high school, culminating in my going out for football my senior year, and I found myself very drawn to Penn State, captivated by the legacy of Joe Paterno and the blue-and-white pride that defined it.

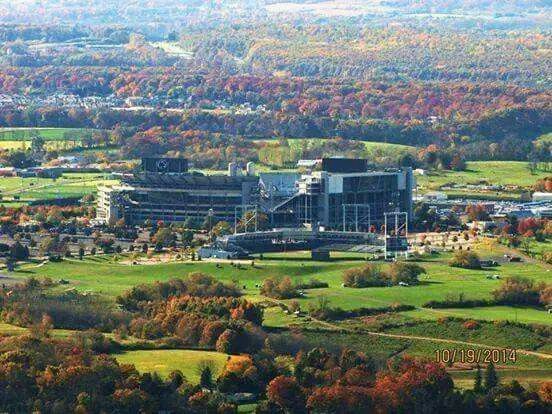

In the years just prior to my tuned in, Penn State had soared to new heights, claiming two national championships and cementing its place as a powerhouse. For that fleeting moment, the Nittany Lions were the best in the gane. State College, just to the west of me, was the heart of this empire—a house that Paterno, a son of Italian immigrants from Brooklyn, had built. He was not just a coach; he was a living legend, embodying the loyalty, community, and tradition that made Penn State more than a football team—it was a shining symbol of our American values at their finest.

I didn’t love Paterno because he won every game. In fact, other than a Rose Bowl win, the program had definitely taken a half step back from the prominence of the 1980s. It was their “success with honor” mantra and Paterno’s commitment to the “kids” as part of his “Grand Experiment” philosophy that had attracted me. Paterno’s stated mission was not only to win on Saturday, but to build men through the game. At least according the brand, the win at all costs attitude was anathema. We are Penn State meant being at a higher standard on and off the field.

The Scandalous End of an Era

There are many good things that Paterno is rightfully remembered for. But history is not kind to those not true to their values and the legacy of “success with honor” is not what any of us wanted as fans from a distance. The man who lived in a very modest house adjacent to the campus—and had donated $4.2 million to the university library—was embroiled in a situation completely at odds with the character of his program. This, of course, being the horrific revelations about Jerry Sandusky—a former Paterno assistant—who was found guilty of sexual abuse of children and was for years according to the allegations.

Shock and denial are a natural response as a defense mechanism. Penn State fandom was more part of our identity where the “We are” was supposed to be a call to a certain moral code and standard. It was supposed to be about more W’s on Saturday and thus it was unthinkable that there was a sexual predator potentially being protected by the program. Those of us who accepted that it happened still wanted to minimize and keep it separate from the man who had preached excellence on and off the field. To this day this is something to be wrestled with—what did he really know and when?

My current stance is that Paterno prioritized the program over everything else. Similar to how religious institutions (like CAM or the Catholic church) too often try to deal with embarrassing issues internally—as a way to minimize fallout—there’s always the desire to save the ‘mission’ by undermining pursuit of the full truth or actual justice. In the end this little leaven of a moral compromise for sake will leaven the whole lump. However, expediency often trumps principles and the putting of reputation first started with Todd Hodne, in the 1970s, when the rapes of the prized Long Island football recruit began to be known. Paterno wanted to deal quietly with these kinds of ‘problems’ and it would blow up in his face at the end.

In my conversations with a cousin, who is a generation younger than me and far less of an idealist, my being completely appalled at fan behavior in the wake of coach Franklin’s collapse is silliness. He says the toxicity is everywhere and, basically, that I should not expect the Penn State football community to be exceptional. Even in response to my own posts on social media some of my friends believe that it is okay to make their vicious attacks against players and future prospects—because apparently sportsmanship is not a goal in the era of NIL money? To me there has been something we have lost in our dignity and self-respect when we pile on young athletes and those who have invested far more than most in the bleachers ever did.

It feels like the culture has been hollowed out. An ethos has been lost. And my own disappointment with the sudden realization of the total absence of anything that actually distinguishes Penn State today, other than a few symbols and slogans, the final dismantling of the Paterno legacy that I’ve protected so long is complete. Why pretend? Integrity was neglected. And the thin veneer of The Grand Experiment philosophy has long ago worn away, we are not what we’ve claimed to be, we’re just another sports ball brand—class and character a mere facade.

Demystifying is the first step in dismantling the Colossus. With the transfer portal and NIL the era of loyalty and commitment to a higher ideal is over. But this shifting is one that goes beyond the football field or Penn State fan base. This is just a microcosm of the failure of the United States of being this “city on a hill” that was imagined by Puritan preacher John Winthrop. The “We are” is a localized flavor of American exceptionalism or the declaration of our unique quality and superiority over others. It is delusion.

It is also decay…

Reclaiming Lost American Values

The erosion of American values, particularly those intangible qualities that once defined community, loyalty, and collective spirit, is vividly reflected in the current state of college football, the influence of Name, Image, and Likeness (NIL) deals, and the broader societal shift toward prioritizing money over meaning. These three threads—Penn State’s football struggles, the commodification of college athletics, and the personal lesson of a child fixated on monetary rewards—converge to reveal a deeper cultural loss that is harder to pinpoint but profoundly felt.

At Penn State, the football program’s collapse mirrors a broader unraveling of shared purpose. The team’s 3-3 record in 2025, with losses to Northwestern, UCLA, and Oregon, has extinguished playoff hopes, compounded by the season-ending injury to quarterback Drew Allar. The program, once ranked #2, has been plagued by self-inflicted wounds—stupid penalties, turnovers, and a lack of team chemistry despite returning key players. The toxic “fire Franklin” narrative, fueled by fans and possibly amplified by wealthy alumni, has created a vicious cycle of negativity. This environment, where success is taken for granted and loyalty to coach James Franklin is eroded, reflects a loss of the communal spirit that once defined college football.

The fans’ inability to appreciate last year’s achievements, coupled with the pressure of high expectations, has turned a storied program into a cautionary tale of how a community’s values—patience, unity, and resilience—can erode under the weight of entitlement and short-term thinking. The prospect of rebuilding under new leadership may spark a recruiting bounce or an influx of NIL funds, but it also risks perpetuating a cycle where only wins and money matter, leaving little room for the intangible pride that once fueled rivalries like the one against Ohio State.

This shift is starkly evident in the rise of NIL, which has transformed college football from a bastion of amateurism into a billionaire’s playground. The purity of the sport, where loyalty to a program and the concept of the student-athlete once held sway, has been supplanted by a system where, as Mark Cuban’s “big number” donation to Indiana University athletics illustrates, wealth dictates outcomes. Fans no longer celebrate players who stay an extra year out of commitment; instead, they view them as paid mercenaries, unworthy of respect or admiration unless they deliver victories.

This also mirrors a broader societal decline in volunteerism and good sportsmanship—values that once rivaled capitalism in shaping America’s identity. The community spirit that made school sports a unifying force has been replaced by a transactional mindset, where loyalty is bought, not earned. This shift reflects a deeper cultural loss: the unquantifiable sense of duty to others or something greater than oneself, whether a team, a school, or a nation.

As the current system prioritizes individual profit over program or principle, it signals a collapse of the traditions that made college football a symbol of American unity, leaving behind a hollow pursuit of wins at any cost.

This same erosion of values plays out on a personal level for me, where my tying my son’s chores to cash rewards has instilled a mindset in him that everything must have an immediate reward or monetary payoff. This mirrors the broader societal trend where wealth is the sole measure of success, undermining the concept of family as a unit bound by mutual care rather than financial transactions.

In cultures like the Philippines, where my wife is from, multigenerational support is just a given, but in America, the collapse of family unit and community has fueled reliance on pay based systems like elderly care, which often exploit the most vulnerable and leave little for future generations.

This shift away from communal responsibility toward an extreme individualism and personal profit reflects a loss of the intangible values—selflessness, duty, and shared burden—that once made America redeemable, if not great. And the rise of socialism, decried by conservatives, is less a cause than it is a symptom of this deficiency, as needy people seek external systems to replace the community support that has faded.

These threads—Penn State’s demoralized and debased fanbase, commodification of college sports through NIL in general, and my own struggle as a father of a teenager to instill non-monetary values—point to a broader cultural decay. The current loss of American values like loyalty, community, and tradition is not easily quantified, as they were woven into the fabric of what it meant to be American, and never before required definition or separate designation.

NIL, like the toxic fan culture or a child’s fixation on cash, is a symptom of a deeper disease: a society that prioritizes money and winning over the unmeasurable qualities that once held it together. This shift, felt more than seen, leaves us grappling with a question: if we cannot identify what we’ve lost, how can we hope to reclaim it?

Records Come and Go—Family Is Forever

After the Northwestern game, a third loss this year, Franklin waited until everyone else—including his daughter—had gone through the tunnel before he strode through. This is likely because he knew what awaited him—taunts and trash being hurled.

In comparison to the stupid entitled clowns, Franklin is a class act. He is the father protecting his family. A standard bearer for Paterno (an Italian surname that means father) or at least the commendable part of the late coach’s legacy. I have seen some of the comments online, one claiming Franklin was arrogant because he had only answered one of their emails or something of similar entitled quality—as if he could just sit responding to every moron harassing him. But the players who played for him are unanimous in their support.

In fact, one of the saddest things I’ve seen is the current Penn State roster expressing their guilt over his firing for “not playing well enough” to please the raving lunatics. They didn’t fail Franklin, the fans failed them and the Penn State tradition.

The players taking responsibility is a sign of a relationship with a man who told them his demands of them as players start with love and end with love. In other words, this was a high pressure environment, expectations were high, and yet it was for their good that he challenged them to be better. And, truth be told, Franklin’s teams punch above their weight. He was a player’s coach and that is why Penn State is bleeding top recruits who were coming to State College for something different under his leadership.

The “fire Franklin” types love to talk about how he “couldn’t win the big game” and yet neglect to mention his teams were almost always coming in as the underdog and with less talent and depth than their top ranked rivals. Or, in basic English, he was coaching them up to the level of the elites. And this a testament to his philosophy that had built on the positive part of Paterno’s legacy—he valued the players for more than the wins or losses and they responded with loyalty and inspired football.

Nobody will ever say Franklin was the best game manager or play caller. But then the online critics keep going back to a couple plays a decade ago. A run on 4th and five against Ohio State or kicking a field goal in a 28-0 Michigan game ending the shutout. But ultimately they were one play from the national championship game last year and Franklin was third behind two other coaches from 2022–2024 with a 34-8 overall record during that span—trailing only Kirby Smart (Georgia, 39-5) and Ryan Day (Ohio State, 36-7) for wins. Good luck finding the guy who will top that after we cut the soul out of the program that drew the talent that we did have. Who will come to State College to be nitpicked and unappreciated?

The toxic part of the Penn State fan base is transactional. They believe their watching a game entitles them to perfection execution and results. I mean, imagine that, a howling mass of ingratitude made of mostly grown men who are apparently that unhappy with how their own life went that everything now is a matter of wins on Saturday. Most did not go to The Pennsylvania State University nor do they have any real investment in any tradition of excellence—like that which was upheld by Franklin’s family approach.

Franklin deserved better. He was not a DEI hire. He is certainly not a terrible coach. It is his players—who carry on his legacy—that actually matter. Penn State football should never be about pleasing drunk Uncle Ricos who failed at life, it should continue to be oriented towards success in life. Truly the few Saturdays under the lights are not a measure of a man. Franklin’s tenure should be remembered as a battle against wider societal decay—where the development of moral character and the building of community are too often sacrificed for the fleeting victories or short-term financial gains.

Both Nick Saban and Urban Meyer, who are legendary coaches, expressed their support for Franklin. And to think delusional Penn State fans believed that they could replace Franklin with one of these two (already past retirement age) by waving a little money in their faces. No, nobody is coming to State College to be unappreciated for producing one winning season after another. We will be lucky to find any successful coach who is tempted by the job—let alone replace all of those who decommitted or will transfer now that James Franklin is gone.

Values Beyond the Scoreboard

In this blog—Irregular Ideation—my struggle with the disconnect between stated values and the values they truly live out. People claim to believe one thing and yet live something else. I’ve dealt with this in the religious and romantic sphere, the disappointment, this false notion that virtue would always win over mere physical or economic superiority. Mennonites teach that the meek shall inherit the Earth or that the first shall be last—these being Christian concepts about the kingdom of Jesus. But the reality lived is always different from that ideal preached.

The reality is that everyone is in it to win it. Yes, even that sweet and submissive young woman doesn’t date no scrubs. Sure, maybe a pious individual will adjust some language or settle on one rather than playing the field, but ultimately they’re going for the status or strength and attractiveness everyone else in the world pursues. Some overestimate the market value they have, but even in love we are being self-sacrificial or altruistic. We’re motivated by hormones and sexual desires—often things we’re not even totally aware of behind our wall of moral rationalizations and narratives.

With denial of this is the delusion that good things will happen to good people. We tend to confuse physical beauty with virtue as it serves our own carnal desires to see them as one and the same. I mean, who wants to say the quiet part out loud by admitting they picked Joe over Bob because he was taller or had charisma? We may say things about nurturing or character traits but this is code for nice breasts and big biceps. So what I am getting at is that we dress all this stuff up as something it is not and revelation of what is underneath is not debasement—it simply exposes what always existed.

From Paterno trying to bury the truth about Todd Hodne to the firing of Franklin, the true ruthless nature of college football culture is revealed.

Beaver Stadium rises up from the farm fields of Happy Valley, a monument to Pennsylvania pride, like the “city on a hill” of American exceptionalism. But success was not built on anything different here as it was anywhere else. What is buried is the reality it is always about aggression, financial gain, and wins. The Grand Experiment failed and Penn State had to be like everyone else if it wanted to reach the top. Furthermore, there is a sense in which every program becomes a sort of family or builds men—Paterno was only unique for highlighting this.

Are there values beyond the scoreboard?

Is it a zero-sum game?

Yes and no. Friedrich Neitzsche describes “slave morality” or a system of ethics that reverses what we naturally value and then says this denial of reality is virtue. Woke is a manifestation of this, where they attempt to turn the world on its head and celebrate obesity, ugliness, criminal behavior or lack of ambition—and create an artificial reality—rather than deal squarely with the world as it is. Body positive isn’t going to spare you health consequences if you’re obese. Fair or not we must at some point deal with the cards we’ve been dealt and rise above our station or accept what we are. Mutilation of yourself to be something you’re not ends as badly as well. There really are no shortcuts to success or Uno Reverse cards to play—it is what it is on the scoreboard that matters to the world in the end.

Ultimately we also have our limits. We need expectations to match our abilities or we’ll end up in a spiral—always chasing what is beyond our reach rather than just building on what we have. I’ve seen it many times, those who leave a consistent and reliable partner, thinking they’ll do better out in the market, only to find out that (yet never will admit) that their discontentment played a trick on them and they had it better before than after. Not everyone can be a National Champion every year—it just isn’t possible—but we can have a family or community that respects all members and seeks only their best rather than tear them down.

So maybe Penn State football does need to be dismantled and rebuilt to be great again?

It could be that, like the children of Israel in the wilderness, we’ll need this generation to pass so our children can enter the promised land?

If the foundation laid has led to this ugly spirit of entitlement then it was flawed. We might need to decide if football is so important we will lose our humanity or the immeasurable qualities not displayed on a scoreboard—for a “big game” win that won’t matter in a year or two. What does it truly matter if we gain the and lost our soul?

A race to the lowest common denominator is the end of civilization. Despite my lament above, I don’t believe life is all about money, sex and power—which ever order they come in. I still believe my elderly grandma had a beauty that was unsurpassed and morality is not just a smokescreen for our failure to be the best. Maybe the impossibility for me is possibility for my children. I cannot stay disillusioned. But, like I did in finally leaving my religious roots, I may need to also bury that delusion of Penn State excellence both on and off the field.

Maybe the failure of The Grand Experiment was all Paterno’s own personal failure? Or maybe the message never went beyond the young men who loved him like players love Franklin today. But the Colossus now lies in ruins making me wonder if it was ever great to begin with. They didn’t just fire Franklin—they pushed over what remained of an ideal for sportsmanship, they’ve fully demolished the mythology that so inspired me. A giant ‘moral’ idol is gone—will something real rise up in its place?